Why the Tenor

The allure of the tenor

The saxophone is a strange instrument. Truly in every sense! Not quite a brass instrument but also not quite a woodwind. It uses a reed but can project a laser beam of sound just like a trumpet. It is a new instrument in the canon of musical developments despite feeling a little dated when compared to the synth-scape sounds available in every DAW. It is personal and expressive in a way no other instrument truly captures. (The voice reigns supreme but we were all chasing Ella anyway) The saxophone owes its collective mythos to the great practitioners who have come before. I wanted to recount some of my favorite albums/online videos that completely blew my mind when I was starting out on the horn. There does not seem to be a limit to where the saxophone can be taken and there is plenty of inspiration out there!

Michael Brecker: Time is of The Essence

One of the few albums I had purchased back before the internet destroyed music sales all together. One of the great things of owning so few albums was I wore out the album. Every song, every solo, and every part were ingrained in my ears. A different type of listening that I should invest more into again.

John Coltrane: John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman

No one can play a ballad like Coltrane. My reference when it comes to these tunes.

David Sanborn: Upfront

I wouldn’t know it until later, but Sanborn was a definitive part of the Brecker Brothers projects; a group which has its own massive stamp on jazz history. I was originally drawn to Sanborn’s force behind the horn and at the time, the only “pop-esc” saxophone player I liked. Of course he was the great player on David Bowies albums as well.

Chris Potter: Gratitude

Not only an incredible display of pyrotechnics on the horn but a launching pad to discover the great tenor canon that came before. Each song a reference to a player who Potter was drawn to during his development.

Kenny Garrett: Triology

Trane for Alto players and for many Triology was their Giant Steps. Kenny has a sound that many are still chasing to this day.

David “Fathead” Newman: Fathead

I don’t see much chatter about this album, but I never skip this one if it comes up on my rotation. Great solos, soulful melodies, and tight arrangements all to the masterclass songs that are Stevie Wonders discography.

Eddie Harris: Cool Sax, Warm Heart

Such a soulful banger. If you only listen to one song, please let it be “More Soul, Than Soulful”. A masterclass on playing the perfect amount without overplaying.

Charlie Parker: Bird with Strings

No one does it like bird and this is him at his best.

Immanuel Wilkins: Omega

I wanted to slip in a newer obsession to the list. Wilkins not only has a lush sound that is as flexible as it is lush; his through composing is so captivating to me in a world of songs that seem to lack any patience whatsoever.

Some live concerts and recordings which I frequent to this day for inspiration:

Making Language Feel Good

Jazz vocabulary and its ability to transcend notes on a page

Title Image: Melissa Aldana; Photo by Ebru Yildiz/Blue Note Records

I have always been enamored with a poet’s ability to effortlessly convey feelings, meaning, development, and subtext while also engaging the listener. I believe the same is true for great improvisors/composers.

I always found it interesting that you could play the “right” notes but have the moment still land flat when composing. Why does this happen and how do the best improvisors pull off good feeling lines?

I think a great example of what good language should “feel like” came up in a Pablo Held interview with Chris Potter. Potter recalls a story about Ornette Coleman being amazed by his vocabulary and almost inhumane ability to convince the listener that what he just played is exactly what his ears wanted to hear. Here is a clip from the podcast of Potter retelling the story:

*From “Pablo Held Investigates” interview with Chris Potter

So What does this look like on the page?

Here are some examples from tenor saxophonists who are playing lines that feel just right to me! Lots of these examples are from some recent transcriptions I had been working on so forgive the bias of a select players and modern examples. A good reminder too that good improvisation is not limited to “Jazz” or the straight ahead tradition. There is great music being made by all kinds of people if you are adventurous enough to seek it out.

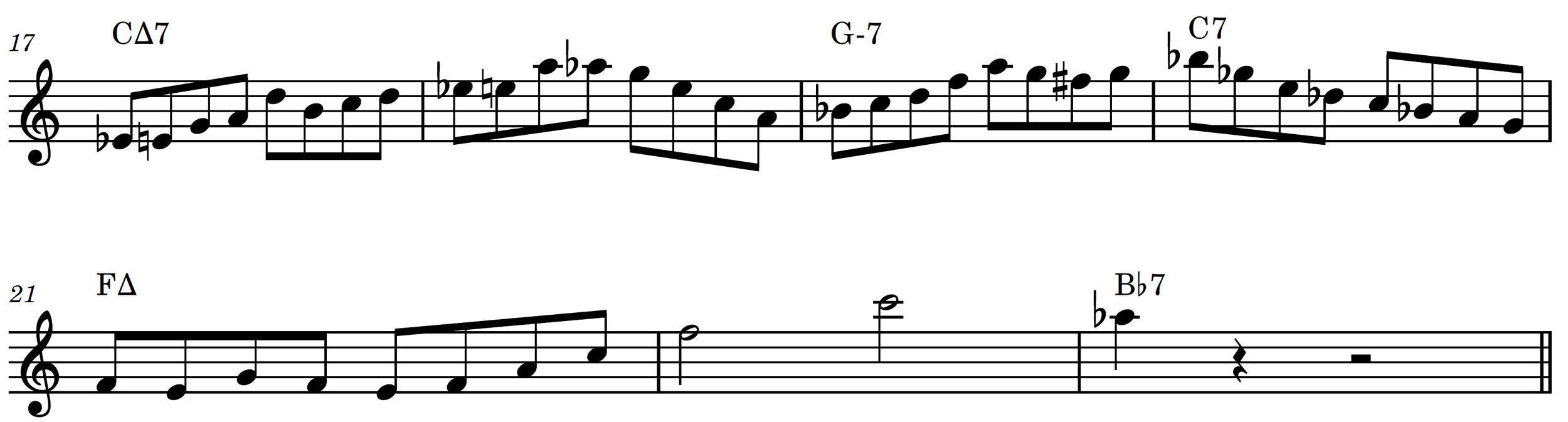

Michael Brecker on “Confirmation” off Three Quartets:

Brecker is swinging hard while also showing his mastery of BeBop language by landing on strong chord tones and utilizing chromatic approaches to said tones. Brecker encloses the 5th of C right on the third beat allowing for an A minor arpeggiation downward. He almost mimics the first phrase in the second bar but this time lands on the second beat with a strong chord tone in B minor. The rest of the phrase is diatonic with a catchy ending to land firmly in G. It is important to note that the last note played in each bar composes in itself a half step line leading to the tonic. Long form voice leading mixed between other movement.

The fast sixteenth note moments give energy to the language while he closes with a classic diatonic phrase. The articulation Brecker is using is punctual on the first beat of each bar leading the ear naturally through the iii7-V7/ii-ii7-V7-I

A lot of the time we see lines that are comprised of eighth notes only. This is not inherently bad since it is a go to for a reason. Eighth notes offer great sense of time and lock nicely within a swing groove.

Mixing in other rhythms helps give direction and dynamic flow to a line. When I talk to someone I usually don’t deliver words with a singular speed as context and delivery matter so much in human communication. We should also apply the same when communicating music to others! This is why tone is also so important on any instrument. Good tone alone can communicate so much just as our favorite narrators say so much with the simplest of words.

Brecker again over “Confirmation”:

Brecker is executing clear ideas at a blistering speed here over the A section. Arpeggiating a B minor chord over D minor is great since it is hits the 6, 1, b3, 5 scale degrees. The jump to D# sets up for a delayed enclosure of F natural that comes on the G7 chord. This then closes with a classic #9, b9, alteration to land on the 3rd of C Major. This line floats for a bit until the D# where it really clicks into a nice V - I figure. Even better is the clear articulation Brecker is using which helps make the line punch out just like his note choices.

Lots of classic Jazz language are blocks of simple material executed at a blazing tempo. Nothing feels better than fast lines that perfectly match the groove. Groove first, notes second!

Brecker on “Pools, Steps Ahead, Live in Copenhagen”:

One of my favorite live performances ever with a crystal-clear live track. In the smaller opening section, Brecker laser beams out this great line over B13.

Again, we can see an enclosure to the B on beat 4 which then chromatically descends to an F natural. He then precedes to superimpose F7 that is mainly utilizing a mix of the dominate and major bebop scale. F7 works here as a standard tritone sub if we were to break apart the B7 into a ii-V (F#-7 | B13). After implying F major, he chromatically reaches D# (Eb if I was thinking about F7 over B13) and then to the D natural. This gives some goal posts of sort so the F7 sound he is going for isn’t entirely diatonic. The movement down half steps separated briefly by a structure is nice voice leading.

The end of the (F7) is a enclosure of the 5th of E7 to B. Played slowly one would hardly think this is a tricky line but Brecker is playing this at a lightning pace. In the moment it sounds so intricate and complex, but Brecker is eloquently using foundational harmonic language to shape a line he clearly spent countless hours perfecting.

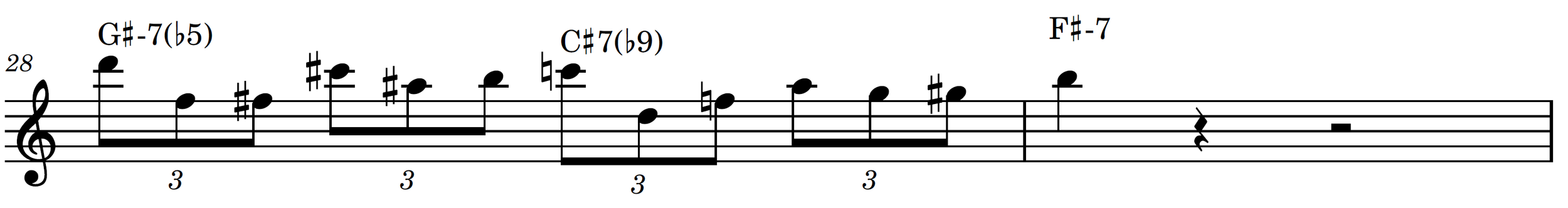

Chris Bittner on “Tea for Two, Live at Smalls”:

Here Bittner creates an extended line that floats so nicely over the changes and ends with a great little pause as the band sets up for Bittner to continue the momentum he has building. Beginning with a Charlie Parker line on G7, Bittner utilizes a b9,#9 and lower neighbor to get to the 9th of C-7. More diatonic playing leads to the Eb^7 which oddly leaps down to a B natural. The oddities continue when Bittner continues to ignore the D fully diminished seventh and encloses a C. I believe Bittner is forgoing the Eb^ and D diminished and thinking more along the lines of an anticipation of C minor. The jump to B natural over Eb^ is a nice sound and gets us to the C as I mentioned above. Bittner then plays a broken C- triad which continues the line in C-7/Bb. C-7/Bb can also be thought of as C-11 but in this case it is notated for smooth bass movement downward into Ab7. Within Ab7 land we find more oddities. He chooses to enclose F# and then B natural which begins and repeats a B^ triad. With dominate chords it is common to superimpose the other 3 dominate chords found in the minor matrix (Ab7, B7, D7, F7). These dominate chords are interchangeable because they share either the C → F# | A → D# tri-tones. (Dan Tepfer has a great video entitled “Tonal Harmony in 3d” which explains the tri-tone interchangeability of dominate chords and why it works) …

Either here the B7 is being thought of instead of Ab7 or Bittner wanted to think of Ab-7 over Ab7. No matter the naming technicalities as it works to great effect especially since the harmonic movement is quite fast.

Finishing up the line Bittner implies G7(b9) to get to the C-7 which quickly turns into F7 a beat early with the use of the b9,#9 motif. Bb^ comes naturally next as the tonic.

What I love most about this snippet is how fresh the playing here feels. Not only is Bittner making the changes but also subverting them slightly in order to provide nice voice leading in his lines and enclosures. His doodle tonging is also great and jolts out emphasis without compromising speed. It is nice to see extended lines played over bar lines or extended past 4 bars. Many developing improvisors will get stuck in rigid phrasing. It is hard to think so far ahead in a song form. Try starting and ending phrases in awkward spots. It is a challenge but might free up some frustration as you will be forced into situations that you previously were not privy to. Lots of material to practice over a single tune!!

Chris Potter on “Cherokee”

Cherokee is a classic tune that has become a cornerstone of many jam sessions. What I love about this section Potter plays is how clear and powerful these lines feel. Every note feels loved and essential to the line. The first two bar potter uses a C^ bebop scale to create some light tension in Major. When G-7 is reached he continues with diatonic playing and a raised seventh to confirm the G- tonality. Nothing crazy yet but solid arpeggiation and chromatic approaches. Over the C7 Potter inserts F#7 language in the first two beats and then lands on the fifth of F two beats early. He continues to blow across the bar encircling the root note before shooting up the F^ triad. The break in eighth notes allow Potter to outline strong chord tones and land on Ab which is exactly what a bass player might play. A → Ab is one of the few note changes between the two chords so it feels strong and functionally all at once.

Potter is one of the best composer alive because of the natural feel his choices seem. A lot of this comes down to the mastery Potter has over the instrument. The entire range of the horn feels full and stress free for him. This particular example is not a good example of his use of range on the horn as the line sits perfectly in the “sweet spot” for the tenor BUT there is no stutter between the ear and fingers for him and it comes across crystal clear.

One of the biggest issues improvisors have been the medium in which they are improvising through. There is a trend in different instrument clichés because different instruments simply have their quirks. The development process to excellence takes a long time and undoubtedly the way music is learned alongside the development of an instrument are intrinsically linked.

Piano players are harmony gurus.

Saxophonists are eighth note rocket ship outside the key center players.

Drummers see the world through poly rhythm.

Anyway…. why do I bring all this up over eight bars.

Potter is a great improvisor because he sounds like a saxophonist without sounding like a saxophonist. On to the next example!!

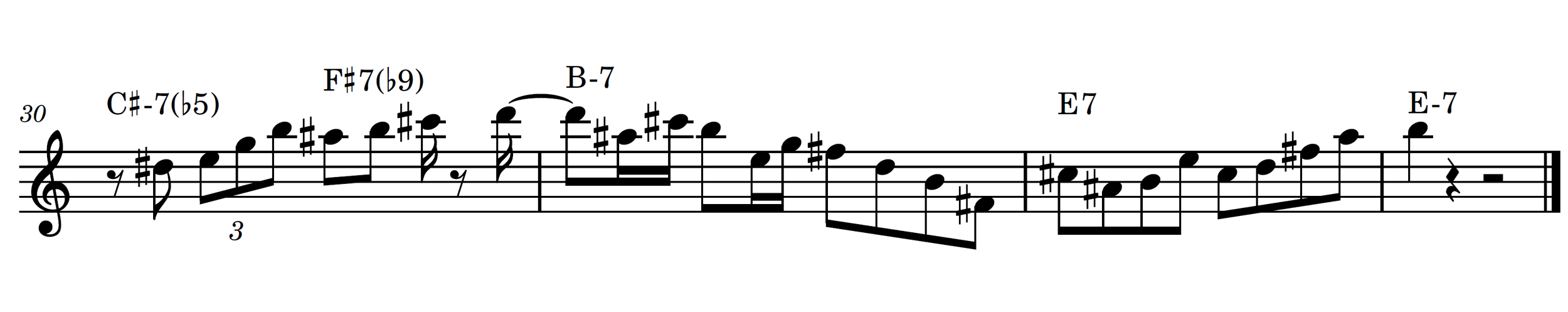

Chris Potter on “I Should Care” from NPR Show “Piano Jazz”

A great way to think about half diminished chords (in the context of minor ii-V-i’s) are as minor sixth chords instead of diminished. In this case E-6 instead of C# half diminished. I like this approach since half diminished is not as strong a sound as fully and sometimes can be limiting (mentally) while trying to make one’s way to the minor i.

Potter begins by shooting up E minor and landing on the 3rd of F#7(b9). He then anticipates the B-7 while playing the 3rd on the + of 4. This is particularly nice since he begins tonguing very sharply in this moment. The gap between C# and D feels even more distant and dramatic then the page would have one believe. To continue the line, he encloses the root and fifth with chromatic lower neighbors. He keeps it simple with only a single chromatic approach to the 5th of E7 before shooting up again to 5th of E-7.

What I like about this line is the feeling Potter is putting behind the notes. He is swinging his ass off here. Ghosting lower sections of a phrase and popping out on strong chord tones is textbook swing and bebop playing. Visually, the line has a nice Up - Down - Up movement to it. For my tenor players this is the sweat spot range that rings the best. It is always advantageous to play in the extreme octaves of an instrument for variety. All the great modern players are extending their compositional range. Nothing wrong with swinging in the goldilocks zone though!

Chris Potter “I Should Care”

Last example I have here is a little different. The harmonic framework is a minor ii-V to F#-7. Potter is setting up a digital pattern that alternates every triplet. Potter starts on the b5 of G#-7 and approaches the 7th chromatically. Then a diatonic enclosure is used on the third. The next two beats are similar but not exactly. The major 7th on a dominate chord is odd but there are no rules here! The F natural is also not exactly approached chromatically and instead jumps from the b9 to the third. So far the shapes are similar but not quite exactly the same. The last triplet is similar with a diatonic enclosure to the 4th of F#-7.

I love how it sounds like a digital pattern but with a couple minor tweaks to address the harmony. If you were to take away everything but the downbeat in each measure; you would be left with is D → C → B. Even better is the beginning of each triplet represents a very elongated enclosure with D → C# → C → A# → B. These lines feel good because our brains hear everything Potter plays here, but also subconsciously feel the walk down he is developing.

Melissa Aldana one time revealed a technique she uses to work on composition that utilizes a technique that is reminiscent of these long form enclosures. She takes a solo she is learning and will erase everything beats 1 and 3. Then will fill the gaps with her own material. What is left is the foundation building blocks for navigating a harmonic passage but now it is up to your own devices in order to make those foundations make sense in context. Thank you Melissa for that one!!

This became a much longer write up then I originally planned. Wanted to get some thoughts down that I had been thinking about for a while. Hopefully something in here is worthwhile to those who might stumble upon it. Composers are always seeking and the journey is never ending. Keep working and enjoy the process!!